Susan Wright, Texas

Matt Rainwaters is an editorial features photographer, based in Austin, Texas. Photographer Lance Rosenfield told me, “Matt is a specialist at making portraits through bullet proof glass.” For the past few years, Rainwaters has been the go-to-man in the lone star state for interview-room portraits. Collected, these portraits are the series Offender.

As well as Texas prison portraits, Offender includes some images from Rainwaters’ 2010 trip to Guantanamo.

Of Rainwaters’ Guantanamo images, I have never before seen photos like his shots of magazines with crudely redacted images of women inside the pages. The layers, scrawls and obvious surface of those images of images seem to encapsulate the malevolent drudgery that is the deadlock between disfunctional fundamentalism and more disfunctional American legal standards. When two resolute systems that cannot accommodate each other an create faint-compromise, they do so with results of zero utility. Perverse and pathetic.

Unfortunately, when I spoke to Matt, I wasn’t familiar with the redacted-image magazine images, so I didn’t ask him about them. Darn! I hope they spark some inquiries of your own.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

PP: Recently, I spoke with Alan Pogue, a documentary photographer in your home city Austin. Alan said it’s easy to get a photograph in a visiting room but if you need to get inside the living quarters and inside Texan prison facilities you pretty much need a lawsuit. What do you think about that?

Matthew Rainwaters (MR): I’d say that’s fair. Getting access to the visiting rooms is fairly easy if you have a commission and if you have the media contact. Getting beyond that though I’ve never been able to.

The writer I work with and I have had great ideas for stories but getting past the visiting room is not gonna happen. There’s been times when literally I could have walked just past the line and made a much more compelling portait, but it’s just not allowed.

PP: How does one get access to the visiting rooms?

MR: If you go to the Texas Department of Justice website there is a ‘media’ section. Contact the media liaison with details of the publication that you’re working for. Once you have the commission, you tell them the story and the prisoner that you’re planning on working with. The negotiations are straight forward.

PP: In how many Texas prisons have you made portraiture?

MR: I’ve been to various facilities in Hunstville, TX; one in Palestine, TX; and I’ve been to four different facilities in East Texas.

PP: Are there any limitations on the equipment you take in?

MR:You are subject to a search every time you go in. I typically have my lighting kit – two strobe heads, a bag with stands and various modifiers, reflectors, cloths, back drops. I’ve never had a problem getting kit in and out.

PP: How do you shoot through reflective bullet-proof glass?

MR: There’s a few tricks that you can use. Sometimes a polarizer will help. Sometimes if it’s a small enough booth I can have an assistant stand behind me with a dark cloth and that will cut down on reflections and then from there it’s just understanding the fundamentals of photography. Lighting, contrast, and trying to work with the available light.

Trying to use a strobe through glass is next to impossible.

From there it’s just talking with your subject, getting to know them, and then trying to effectively communicate their story that the writer is also telling.

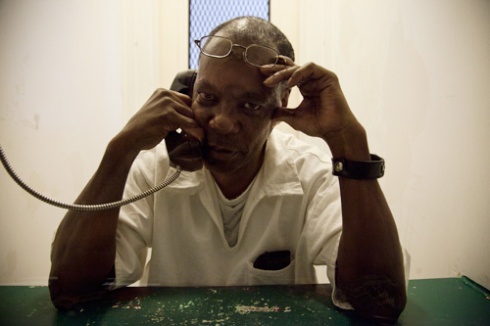

Wayne East, Texas

PP: Can you describe each of your subjects and their particular stories?

MR: I photographed Wayne East. He was convicted of a murder. This is a pretty compelling story. He spent 19 years on death row before a woman started championing his cause. Not incoincidentally, she was the victim’s cousin who believed that East is innocent.

She raised a bunch of money, spent a lot of her own money and basically petitioned to get him off of death row. He was recently paroled. after 30 years for the crime.

PP: It wasn’t a wrongful conviction?

MR: East has always said he is innocent. The question remains: Was he really guilty or is he innocent as she also believes?

The other story I was really close to was that of Susan Wright (top image). My images ran in Texas Monthly for an article titled 193. She was convicted of murdering her husband by stabbing him 193 times.

Susan Wright, Texas

MR: The story goes that Wright’s husband would come home and beat her. The defense attorney never brought up battered woman syndrome.

Well, one day he came home and started rough-housing with their kid, slapped him around, and that’s actually what drove her over the edge and she tied him to the bed and then ended up pulling a knife out and stabbing him 193 times. This whole idea of battered woman syndrome and her being psychologically damaged from years of abuse was never brought up during the defense. So she was up for an appeal for parole and I believe that’s still pending. I don’t know how that’s played out.

PP: There’s another compelling portrait of a female in that story was it the prosecuting attorney or the DA?

MR: Kelly Siegler, prosecutor in the Harris County district attorney’s office.

The court proceedings were aired on Court TV and Siegler was a controversial character because she was very theatrical in her closing arguments. She ended up tying one of her law assistants to the table and climbed on top of him and proceeded to count out 193 stabs, every single one she simulated with her pen. All on TV. A lot of people believe that those theatrics are responsible for convicting Susan.

Kelly Siegler, District Attorney prosecutor, Texas

PP: What was your first prison shoot?

MR: Steven Russell. You may be familiar with him from the movie I Love You Phillip Morris starring Jim Carrey as Russell.

Russell is Texas’ most notorious escape artist. He’ll be in prison for the rest of his life, even though he was originally convicted of a white collar crime. Russell fell in love with a man in prison, escaped to be with him, and then continued to escape over and over again. So what could have been a relatively short prison sentence has been compounded by the crime of escape four times over.

Russell was in the most maximum security prison – the Michael Unit out past Palestine. He has one hour of sunlight each day. He’s locked up in the same way as the most violent offenders, although he’s a completely non-violent offender.

All four times that he escaped were completely nonviolent too, so it’s sort of tragic. Does he deserve to be there? You know, that’s questionable. He did escape but it’s a sad story nonetheless.

Steven Russell, Texas

PP: Let’s move from the US to the US’ outlying territories? When did you got Guantanamo and why?

MR: I went to Guantanamo for Esquire UK in March, 2010.

PP: For how many days?

MR: It was a three day stay on the base.

There’s a lot of misconceptions about Guantanamo Bay. The media portrays it as solely as a detention facility on the coast of Cuba but what I didn’t realize until I got there it’s been a functioning military base since 1906 – a lot of it’s operations have to do with immigration and refueling point for US allies.

MR: We did the media tour of the prison facility. We went to some of the different camps. Saw how, in some cases, some of the inmates live communally, in other cases some of them are locked down. There’s definitely a lot of secrecy still. It’s not as transparent as they would have you believe. There’s some camps that you don’t have access to at all and there’s some camps that they don’t even admit to existing on the island and they don’t show up on any maps. But it’s been proven that there are certain inmates that are held there in a mysterious location.

MR: What is extremely frustrating about photographing at Guantanamo Bay is the strict security protocol. At the end of every day, you sit down with an officer and they look through every single photo.

Sometimes very arbitrary reasons or sometimes very good reasons, they will delete a photo. If they don’t like the way it may represent the prison then they’ll delete those photos too.

Every single photograph goes through this “filter.” I had maybe 60% of the images I shot deleted before I came home.

PP: Is it fair to ask if there’s any points of comparison between Guantanamo and the Texas prisons? Did you feel as though the monitoring is different? Did you feel as though the administrations understood your role as a media person differently? Do you find any irony in the fact that Guantanamo is one of the most secure and notorious prisons in the world but they provide these three days media junkets, something state prisons do not provide?

MR: Within the Texas prison system we’re there to photograph a specific individual. So you’re led into an interview room or booth. I’m there to take a photograph of that person whereas in Guantanamo Bay the subject isn’t a specific person it is the entire facility.

PP: But in both cases, for different reasons, the authority is media savvy and happy to work with you?

MR: Yes.

Guantanamo Bay a lot of people believe, and quite possibly rightfully so, should be shut down because it is a publicity nightmare for the United States. Everything they’re trying to do with the media at Guantanamo is to try and show how fair, how honest, how transparent, everything is and they’re really trying to deflect this image of it being a detention facility that practices torture.

The institutionally genius part of Guantanamo Bay, from the administration standpoint is no-one is stationed at Guantanamo Bay. People are only deployed to Guantanamo Bay, so no-one stays there for longer than a year-and-a-half and that goes to the highest ranking people, including the admiral who’s in charge of the Joint Task Force.

So, when you ask them about issues of torture or enhanced interrogation methods everyone can default stock answer over and over again. We kept running into, “I don’t know, I wasn’t here.”

Institutionally it’s set up in that way and that was probably the most frustrating thing as a journalist. No one can tell the whole story. The institutional memory of the place is at best a year old.

PP: Your work has a very distinct look. So, how would you say it fits in with other photography made in prisons? And I’m asking that in terms of like who has the power? How does it inform the public?

MR: I’m photographing individuals and as an editorial features photographer. Portraiture is mostly what I do so I’m trying to set up a dialogue with my subject that is fair to them and it’s honest to the story. I have to quickly learn how to make people comfortable, disarm them, get them to open up to you so that you can be fair and honest to them.

I typically have an hour to work with a subject, it’s a different thing than say a documentary looking at a place over and over again. I’m working work within the confines of limited time and semi-limited knowledge of the person and trying to break all that down and create a portrait.

PP: What is the reaction of your subjects? What do they think will come about through your interaction with the camera as a mediator?

MR: A mixture of skepticism and hope. They hope that telling their story will better the legal decision that may be looming. Maybe it’s a plea for an appeal or they just want to tell their story. Maybe they feel like they haven’t been able to tell their side of the story?

But there’s also skepticism because they don’t know necessarily the turns that the story may take and they don’t know what the recent side of the victim’s story, nor the reactions to it.

Imprisoned subjects can be guarded at first. Usually, there’s 10 to 15 minute window where you’re talking on the phone through the plexi glass. I’ve got my camera just sitting there and I’m not taking photos, just taking the pulse of the person and getting to understand them … and that will dictate everything.

Wayne East, Texas

PP: You’re building what could be loosely characterized as a portfolio of visiting room prison portraiture. Is there a common aesthetic that runs through those that you’re either conscious of or you’ve just started to notice as these projects mount up. Not in a pejorative sense, I want to describe Offender as creepy. Is that okay?

MR: Well, it’s definitely that institutional aesthetic – you’re so confined with time and space you literally have to learn to make do with whatever’s thrown at you.

Now that I’ve done it quite a few times I know what to expect; “Am I shooting through plexi-glass today or am I shooting through a screen? Do we maybe have an open room to work with which maybe means I can actually set up a back drop and maybe a light or two? Am I free to interact with the person without talking on a phone?”

It’s a dark subject but it’s also mostly working with honest stories – fascinating stories, but yeah, creepy at times. Ultimately, these are stories that need to be told and that’s why I enjoy photographing, I believe it’s some of the most honest work that I do.

PP: Thanks Matt.

MR: Thank you, Pete.

“Matt is a specialist at making portraits through bullet proof glass.”

There are specialists, and then… there are Specialists!

LikeLike