Following its 66th AGM earlier this week, Magnum Photo Agency announced that Olivia Arthur and Peter van Agtmael are its newest members.

Good choices. Peter’s a nice guy and was kind enough to offer up images and his first hand account of a story we weren’t even sure was a story. I have not met Olivia Arthur. She is a photographer I’ve admired for a long time. I am amazed (and a little embarrassed) that I’ve not mentioned her photography before here on the blog.

Jeddah Diary is one of the standout photography projects of recent years. Now is a good time to feature some images and publicly applaud Arthur’s tenaciously delicate observations of Saudi women.

In 2009 , the British Council invited Arthur to conduct a two week photography workshop with women in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Jeddah Diary does not feature the photographs made by Arthur’s students; the products of the workshops largely remain a mystery. Instead, Jeddah Diary is comprised of Arthur’s own fragmentary observations and photographic concessions that emerged as she tried to make sense of depicting a veiled subject.

The cultural and religious traditions of Saudi Arabia restrict the opportunities to photograph many women who are not wearing the abaya. As I understand, both Arthur and the women did make images of each other unveiled, but the images could not seen or distributed; conceived of, but not shared.

Arthur says that her first impression of the city of Jeddah was that public spaces were empty. Perhaps the important (human) interactions went on behind closed doors? The abaya is only one form of cover in Saudi society. The fabric of architectures, court yards and corridors bend and shape relationships.

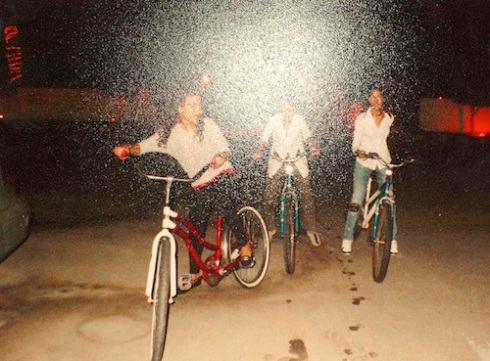

Saudi society thwarts many of the visual relationships — photographer/subject and photographer/audience — that are taken for granted in secular countries and in less traditional regions of the Arab world. As such, Jeddah Diary is a collection of work-arounds and solutions; rephotographed portraits, limbs and parts of people, plays with spotlight and night shadow to obscure identities.

The parameters of negotiation between Arthur and the women about what could be shown trod, at times, strange ground. After using flash to anonymise her subject (above photo), Arthur showed it to the women and they responded, “That’s great, but can’t you show a bit more of her eyes so people can see how beautiful she is?” asked some of the women.

These unique discussions led to photographer and subjects becoming close friends. Arthur says:

“On my first trip to Saudi I worked in medium format but this photo was taken on my second trip, using a little Panasonic Lumix. Because this was the sort of camera the women themselves used, when I used it they started to stop seeing me as a photographer and saw me instead as a friend. At the beginning I’d been clear with them that – as professional photographer – I wanted to show these pictures, but the funny thing was that when I switched cameras they relaxed and I ended up taking pictures that afterwards they didn’t want me to use.”

For me, the most compelling images are those of women veiled and in everyday moments; sitting on a kitchen counter, in a restaurant; fooling around while sharing tea. These are intimate events and the challenge to depict a hidden subject can be solved the moment one abandons a battle against restraints. Arthur’s interactions and discoveries are central to the book Jeddah Diary.

“I just thought, let’s take people on the journey that I went on, and show how confusing and contradictory it can be rather than trying to explain it; that’s the point when it finally made sense to me.”

And because of Arthur’s efforts, it starts to make sense for us. As Antone Dolezal remarks in his review of the book, “Jeddah Diary tells a story that could only be informed from a female perspective … a story both hidden from the world of men and only privately discussed in the world of women.”

Jeddah Diary, by it’s nature cannot make full sense to us. Or rather, if we adopt our usual insistence to see idenifiable faces, and know names, and have place and date stamps attached to each image, we’ll be sorely disappointed. Arthur’s primary consideration was to protect her friend-subjects. As Sarah Bradley notes in her review of the book:

“It’s hard to tell who we are looking at in the images — some girls are named, but we see few faces, and in a small postscript Arthur makes it clear that in no way should one infer that the girls attending illegal parties are the same girls depicted elsewhere in the book. Her thank-yous show that many chose not to be named.”

Jeddah Diary is a moment of slippage. It is a document of the undocumentable. In that regard it is also a moment of reflection — and, for me, a cause of sadness — on the fact that Saudi women have limited choices in how they operate in society and interact with the world. Fashion is a flip topic, but clothing is not. It’s a simple point to make, but the abaya limits self-expression. I wouldn’t want to state the degree to which self-expression is limited or even what the results (positive and negative) emerge from a single, designated type of garb for one gender in a society.

The women in Jeddah Diary were, based on Arthur’s report, ambivalent about the project. And, I feel, probably reluctant to think of images as agents for social change.

“I was surprised how few of them had any major feedback. When I was there and tried to ask them how they felt about their situation, they’d say, “You know what – we’re okay” so I’d leave it. They were happy to be in the photographs but they’re not bothered about the comment I’m making on their society.”